The advent of the Internet in general, and tools like Google search in particular, heralded an age in which instant access to all the world’s knowledge would enhance discourse, remove the traditional gatekeepers to information, and lead to greater human flourishing. I remember the aughts being a period of great techno-optimism, with America leading the way and this hopefulness peaking around the time of the Arab Spring in 2010 and 2011, when we were told that social media had enabled activists to topple dictatorships and bring freedom to an oppressive region. (Not quite true, it turns out.)

Alas, the sanguine era wouldn’t last. Things began to unravel as the tech companies morphed into giants with a voracious appetite for profit; the modest gains of the Arab Spring were reversed (in Egypt, the military returned to power in 2013, for instance); and the Tea Party ushered in a resurgent Right, hellbent on revenge and harnessing anger in a way that presaged Trump and the MAGA movement. Before long, academics and others were warning of the “attention economy” and how the algorithms behind YouTube, Facebook, and other platforms promulgated anger, hate, and conspiracy–because those emotions lead to more engagement, engagement means more time looking at ads, and ads mean more profits.

All this came to a head for me last week, when I noticed a random contact on Facebook was posting numerous anti-EV memes, such as this:

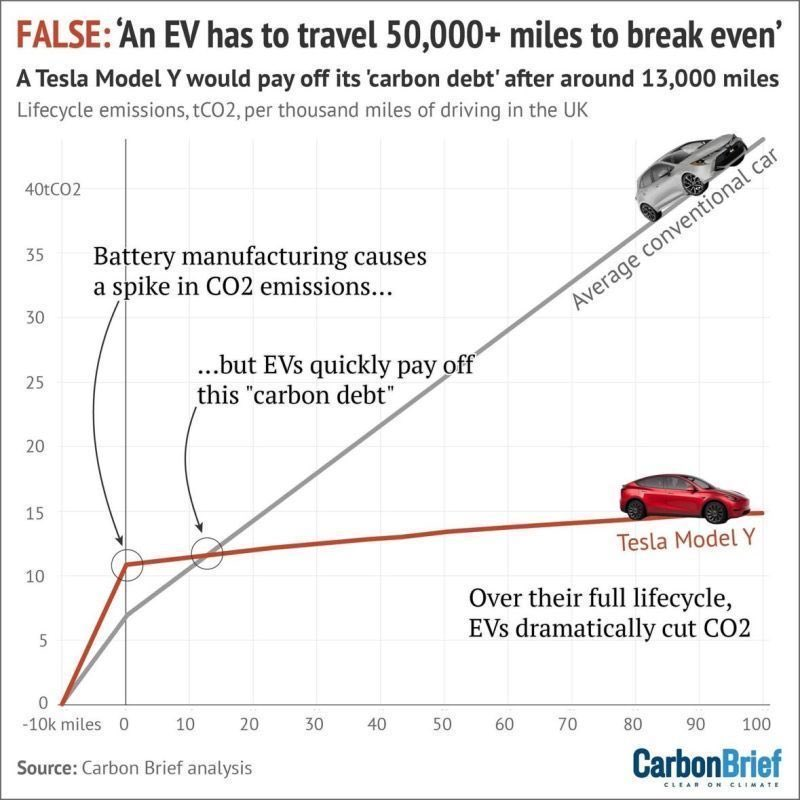

I found this both fascinating and infuriating. First, the memes are flat-out wrong: the reason we want to “electrify” as much as possible–that is, transition to machines that run on electricity–is that it’s easy and cheap to create green electrons and difficult and expensive to create green molecules of liquid fuel. What’s more, heat pumps, EVs, induction stoves, and other electric devices are far more efficient than gas-fueled cars and boilers. So even if you charge an EV on an electric grid that is powered primarily by fossil fuels, it is still less carbon-intensive than driving an internal combustion vehicle. And in any event, the grid is increasingly run on solar, wind, geothermal, nuclear, hydropower, and batteries that store all this clean energy. Second, the memes can be refuted with a simple Google search along the lines of “are EVs better for the climate?” That trivial search would yield easy-to-understand infographics such as this: And third, what strikes me is that the people posting this content are doing so to “own the libs” and / or to feel like they possess some kind of contrarian knowledge–that they know better than the so-called experts calling for electrification. This is actually a logical outgrowth of all this access to knowledge: while people can find scholarly articles with accurate information, they can also find misinformation put out by, say, a fossil fuel industry that doesn’t like EVs and heat pumps. And just as hateful speech is more likely to go viral than nuanced analysis of a complicated issue, so too is it easier to come across simple–and incorrect–content about said issue. Movements like QAnon leverage people’s desire to find easy answers to a complex world and the fact that the Internet facilitates the spread of conspiracies and connecting conspiracy theorists with one another; the QAnon motto of “do your own research” is actually a way to justify shallow conclusions, such as claiming that vaccines have microchips.

And third, what strikes me is that the people posting this content are doing so to “own the libs” and / or to feel like they possess some kind of contrarian knowledge–that they know better than the so-called experts calling for electrification. This is actually a logical outgrowth of all this access to knowledge: while people can find scholarly articles with accurate information, they can also find misinformation put out by, say, a fossil fuel industry that doesn’t like EVs and heat pumps. And just as hateful speech is more likely to go viral than nuanced analysis of a complicated issue, so too is it easier to come across simple–and incorrect–content about said issue. Movements like QAnon leverage people’s desire to find easy answers to a complex world and the fact that the Internet facilitates the spread of conspiracies and connecting conspiracy theorists with one another; the QAnon motto of “do your own research” is actually a way to justify shallow conclusions, such as claiming that vaccines have microchips.

Even though I know the tech companies are taking advantage of human biology to turn a profit, and that purveyors of injustice like oil majors and authoritarians are doing the same, I remain stunned that people can fervently believe in easily disprovable things. What’s worse, facts don’t work, either. The person posting about EVs, in response to my providing a detailed refutation, went on some rant about China that I couldn’t make sense of; and it does no good to read a NY Times article debunking myths about EVs if you’ve trained yourself to automatically distrust the “mainstream” media. Point is, no amount of cajoling or presenting evidence will change his mind, because what he’s looking for isn’t the truth but a feeling–the feeling of being right, of possessing secret knowledge, of bucking the trend.

What are we to do when facts don’t matter–Kellyanne Conway famously spoke of ‘“alternative’ facts”–and vibes rule the day? Where did things go wrong with the Internet and, in turn, society? It seems that access to information yielded a belief that expertise didn’t matter–why listen to elites when we have Wikipedia, when we can find our own answers? The issue, of course, is that Google is not a substitute for the deep knowledge that subject-matter experts possess. The person posting about EVs may not care, but I have a master’s degree in environmental studies and have worked on clean energy for fifteen years. It makes as much sense for him to debate me about electrification as it does for me to question my wife on vaccines: she has a PhD in immunology; two minutes into her explaining the science of vaccines, I am completely out of my depth.

The world is more complex than ever. Being a Renaissance man–scientist, poet, philosopher, engineer, inventor–may no longer be possible. The Internet is really good at allowing us to find syntheses of this knowledge, but it’s also great for finding ignorant rejections of it. Just look at climate change. The greenhouse gas effect has been known since the 1800s, and Exxon Mobil’s own scientists predicted the climate crisis quite accurately way back in the 1970s. Yet 46% of Americans don’t see climate change as a major threat (according to Pew Research) and greenhouse gas emissions continue to climb.

So what’s the answer? I suggest five solutions, none of which are easy:

-

- That same Pew study shows how important the framing of an issue is. 74% of Americans “support U.S. participation in international efforts to reduce the effects of climate change” and 67% “say the country should prioritize developing renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, over expanding the production of” fossil fuels. Talking about energy security, clean air and water, the jobs created by electrification–these messages resonate better, particularly with Republicans, than focusing on reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- There is no getting around the need for relationship-building. Something else the Internet has done is isolate us, physically and emotionally. Algorithm-driven platforms tend to present people with content they already agree with, creating self-reinforcing online communities. At the same time, the appeal and ease of watching Netflix and scrolling through TikTok has played a part in reducing in-person interactions; this is a long-term trend, but one that has accelerated in the past decades. People can change their minds, but only if they hear from a trusted messenger–a pastor, a friend, a counselor. “Armchair activism”–trying to change the world from the sofa–doesn’t work. Attitudes about race, the environment, or homsexuality only change after decades of activism, protest, and deep conversation.

- To my knowledge, Internet literacy is not taught. This transformational technology emerged in the 1990s and then grew exponentially, to the point that “In 2021, adults in the U.S. spent an average of 485 minutes (eight hours and five minutes) with digital media each day.” Yet we’ve never taken time to learn how to identify disinformation and misinformation; how to protect our identities; how tech companies use our personal data to generate profit; and that what we say and do online has real-world implications. This lack of digital literacy means that hundreds of millions of people engage with this vast universe of content with little to no tools with which to navigate it. We are addicted to something we don’t fully understand and are not trained to use.

- Rational people of good will must come into, stay in, and wield political power, which, in this moment means Democrats. Ranting and raving online, slapping bumper stickers on our cars–those things don’t move the needle. But thanks to the voters, Democrats controlled the House, Senate, and White House from 2021 – 2023, and during that time they passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the CHIPs and Science Act. Taken together, these represent trillions of dollars in investment in clean energy, infrastructure, and job creation.

- Finally, we have to find ways to break through the cloud of misinformation, ad hominem attacks, and lies. For example, over two-thirds of voters don’t know about the Inflation Reduction Act, Biden’s signature climate legislation. Republicans have no interest in governing, but they are adept at pounding the public over the head with simple messaging. And despite the Right’s claims of media basis, the reality is that most people get their news from outlets owned by conservatives or those that bend so far backwards to appear neutral, it’s laughable. As a case in point, consider how much time the media spent covering Hillary Clinton’s emails as opposed to Trump’s racism, xenophobia, corruption, and ties to Russia. Alas, I don’t know the answer here: it’s so easy to tell a lie and by the time it’s been refuted, the public has moved on to the lie du jour.

In short, political discourse by meme is no way to maintain a Democracy with a shared common purpose. So long as people’s understanding of the world is shaped by slogans and memes, they will be susceptible to the propaganda of people who only act in their self-interest. Trafficking in nuance and reason is hard, takes time, and doesn’t always work. But that may be the only way, in the long term, to defeat the threat posed by movements that explicitly reject the truth, such as MAGA, anti-vaxxers, QAnon, and more.

Leave A Reply