Introduction to Activism

My introduction to the world of activism took place in 2002 and 2003, in the run-up to the war in Iraq. At the time, I was a seventeen-year-old freshman in college who, while certainly an idealist—I had read Thoreau’s On Civil Disobedience and been influenced by the Romantics, especially Keats and Shelley—I had never been engaged politically. That all changed when the Bush Administration’s saber rattling toward Iraq coincided with my taking a class with a strident anti-war-activist professor.

Soon, I was attending protests, reading anti-war literature, and giving talks; on February 15, 2003, I took an overnight bus from LA to San Francisco and spent the day with over 250,000 people—chanting, marching, praying, and singing against the planned war.

And then, on March 20, 2003 the invasion of Iraq commenced, ushering in an astonishing—and predicted—era of geopolitical instability, trillions of dollars in wasted spending, and immense suffering and death for the Iraqi people and U.S. servicemen and women. As it became clear that our political leadership was going to ignore the voices of dissent in the U.S. and beyond—that day of the protest in San Francisco, “between six and ten million people” in roughly 60 countries demonstrated against the planned invasion—I began to ask myself the logical next question: Why were we failing? And what does it take for social movements to succeed?

The Fundamentals of Change

Unfortunately, many of us, especially activists and other change agents, understand far too little about what works and doesn’t, why some protests fizzle out and others lead to transformational change. The typical understanding of social change goes something like this. Rosa Parks one day happens to get sick of being asked to go to the back of the bus, so she refuses. Her doing so strikes a nerve, igniting the Montgomery Bus Protests. A charismatic leader-in-waiting, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is called in; with his inspiring words and deeds, he helps bring about the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Voting Rights Act of 1965, and countless other changes.

Needless to say, this is not how it works. Black people were working against slavery from the time of the first slave ship from Africa. Rosa Parks didn’t randomly decide to resist; she was the founder of the Montgomery NAACP Youth Council and was “well trained in civil disobedience.” Millions of people worked for decades, if not centuries, to lay the groundwork for the successes of the 1960s: lawyers, activists, organizers, writers, poets, philosophers, singers, soldiers in the Civil War–most of whom will never be known to history but without whose contribution, progress would have been impossible.

Of those that have made scientific and practical study of social change, some of the most notable include Gene Sharp, Erica Chenoweth, and groups like Beautiful Trouble. Sharp, for instance, wrote several seminal books on nonviolent change, including The Politics of Nonviolent Action, From Dictatorship to Democracy, and The Role of Power in Nonviolent Struggle, in which he makes a deceptively simple point:

The rulers of governments and political systems are not omnipotent, nor do they possess self-generating power. All dominating elites and rulers depend for their sources of power upon the cooperation of the population and of the institutions of the society they would rule. The availability of those sources depends on the cooperation and obedience of many groups and institutions, special personnel, and the general population.

Sharp’s conclusion is, in effect, that if people withdraw their cooperation, elites and rulers–be they dictators, authoritarians, corrupt officials, or even bad corporate actors–can be overthrown or forced to change course. Even better, Sharp boiled down his research into 198 Methods of Nonviolent Action that can be used to withdraw cooperation. These methods include broad categories such as “noncooperation with social events, customs, and institutions,” “Symbolic Public Acts,” and “Physical Intervention.” Beautiful Trouble has turned his and others’ work into a highly accessible set of trainings and toolboxes that go through the theories, methodologies, tactics, principles, and examples of nonviolent action.

In their 2012 book, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan argue that nonviolence is more effective than violence when it comes to bringing about social change. Specifically, through an exhaustive studies of social movements between 1900 and 2006, they conclude that

nonviolent campaigns are twice as likely to achieve their goals as violent campaigns. And although the exact dynamics will depend on many factors, …it takes around 3.5% of the population actively participating in the protests to ensure serious political change.

The problem, however, is that neither Sharp nor Chenoweth nor the folks at Beautiful Trouble can explain or predict why a particular movement fails or, if it succeeds, when it will do so. I thought a lot about this issue during the Trump years, when, although we still had a democracy, organizing against his anti-democratic actions was robust and played a crucial role, I believe, in preventing an even worse outcome from his time in power. And now, with the Blank Paper protests against China’s Zero-COVID policy, a renewal of climate change-related protests, and the ongoing unrest in Iran over the death of a 22-year-old who had been detained for “not wearing her hijab correctly and sporting skinny jeans,” I again want to know: Will the protesters succeed? What can we do to encourage and plan for success?

Revolutionary Thresholds

In trying to answer those questions, I stumbled across a fascinating article, titled Now Out of Never: The Element of Surprise in the East European Revolution of 1989, which attempts to explain why successful uprisings, like those that led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, are “easily explained in retrospect” but so hard to predict in the moment. The author, Timur Kuran, argues that preference falsification–a term he coined and defined as “the act of misrepresenting one’s wants under perceived social pressures”–can lead a oppressor to assume that his power is more durable than it is, and the oppressed to believe that far more people support the status quo than they actually do. As a result, regimes like the Soviet Union can persist far longer than people might prefer, but also, under the right circumstances, crumble in a matter of days or weeks.

Timur writes that in any society, each person, regardless of their personal beliefs, must “choose whether to support the government in public or oppose it.” Preference falsification is when the two diverge–when a person joins the Communist Party, say, even though they personally find the Party abhorrent. He notes that people’s willingness to publicly support the regime is not fixed; rather it depends on obvious factors like the economy but also, crucially, on each person’s perception of the size and power of the opposition. We must understand that each person has a different threshold for when they will take the risk of joining the opposition: some will do so at any cost, otherwise will do so once a handful have joined in, but many others will only participate once the protest movement is so large as to minimize the danger of participation. (This is why Chenoweth argues that nonviolence is so effective, because it lowers the barrier to participating in the opposition, since far more people are willing to attend a rally, say, than to take up arms and join a guerrilla movement.)

Timur calls the point at which “the external cost of joining the opposition”–losing one’s job, being arrested–“falls below his internal cost of preference falsification,” a person’s revolutionary threshold. Again, each person has a different threshold: Dr. King’s threshold was very low, whereas someone whose first experience of the Civil Rights movement was joining the 1963 March on Washington likely had a high threshold for action.

In oppressive societies like China, Iran, or Russia, it can be dangerous to express public opposition to the regime. The external cost of opposition, then, is very high: protestors like Alexei Navalny are disappeared, murdered, harassed, and thrown in jail. Moreover, the less inclined people are to express their dissatisfaction with the regime, the less likely they are to support an opposition movement: preference falsification makes it hard for citizens to know the likelihood of others joining them, and most people want to know that if they take to the streets, they won’t be alone.

Imagine a society in which everyone is expected to put a picture of the dictator on the windows of their homes and shops. One day, a restauranteur, having grown fed up with the regime, takes down the dictator’s photo and replaces it with a question mark. Seeing this, citizens will react in a number of ways. Some will denounce him to the authorities, either because they support the regime or see a personal benefit in doing so. Others will smile approvingly but not take the risk of removing the photo from their home. And a handful might decide to copy the action.

Authoritarian regimes respond swiftly and brutally to even the smallest signs of dissent because any disobedience can dispel the perception of broad support. If the regime arrests the restaurateur before the protest can spread, they will raise the revolutionary threshold for all but the most committed resisters. If, on the other hand, they wait until a critical mass of citizens have taken action, a heavy-handed response may further inflame the people, thereby lowering their internal cost of preference falsification. As more people join the movement, the risk to each participant goes down, and before long the regime crumbles.

Timur argues that what makes it nearly impossible to predict when a movement will succeed is that we cannot know what each person’s revolutionary threshold is. At the same time, he gives us a key framework: anything we can do to lower the threshold increases the likelihood of success. In this model, seemingly small, symbolic actions can make an outsized difference because they carry a smaller risk than big, bold actions, thereby making it easier for others to join in. In China, for instance, protestors holding up blank pieces of paper aren’t technically violating any law: how can a censor object to someone who isn’t actually saying anything?

In fact, the protestors are using one of the most powerful tools in the nonviolent activist’s toolkit: what Srđa Popović calls a “dilemma action.” For if the Chinese authorities begin arresting people for holding up white pieces of paper, they look feckless, weak, and paranoid. But if they do nothing, people may realize that the authorities don’t have that much support: protests may grow out of the government’s control.

Again, keep in mind Gene Sharp’s observation that a regime cannot stay in power without the cooperation of the people. Another way to put it would be to say that social change happens when people stop cooperating with the status quo. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) knows this, which is why their response to the protests will likely be a mix of relaxing COVID restrictions and clamping down on protestors. Whether or not this will quell the people’s desire for change will depend on the extent to which their revolutionary threshold is raised or lowered due to the actions of the CCP and the responses of other protestors. (My prediction is that, for various reasons outside the scope of this essay, the protestors are looking for an easing of Xi Jinping’s authoritarian policies, not an overthrow of the CCP.)

What About Social Movements?

But we run into trouble when we try to apply this framework outside the context of authoritarian regimes. How applicable is the revolutionary threshold to tackling the climate crisis, say, or issues like preventing the war in Iraq and abortion rights? The answer is that in a democratic system, the path to change is more nuanced. Greg Satell and Srđa Popović write that successful movements have five components:

-

- They have a clearly defined purpose. A list of grievances is ineffective; calling for a specific change–$15 minimum wage, the resignation of a corrupt official–is more effective.

- They understand their allies, and work to grow their base of support. “Successful movements don’t overpower their opponents; they gradually undermine their opponents’ support…In other words, begin by mobilizing your active allies and core supporters. Reach out to passive supporters, and then bring neutral groups over to your side.”

- They understand who has the power to enact the change they seek. Recently, climate protesters have defaced works of art at museums. While they have gotten people’s attention, these actions are ineffective because museums dont have the power to do anything about the crisis: targeting the banks that finance fossil fuels, the fossil fuel companies themselves, and elected officials makes more sense.

- They build an inclusive movement that allies enjoy participating in and that welcomes new supporters: “Cheap, easy-to-replicate, low-risk tactics are the most likely to succeed. They are how you can mobilize the numbers you need to influence a pillar of power, whether that influence is disruption, mobilizing, or pulling people from the middle of the spectrum of allies, especially if your tactics are seen as positive and good-humored.”

- They have a plan for what happens when they succeed. Articulating a vision of what the world will look like if a movement wins is key, as is being prepared for victory. Now that the Inflation Reduction Act has passed, for instance, we are suddenly realizing that, absent permitting reform, it will be hard to build the new grid infrastructure needed to carry clean energy from where it’s produced to where it’s consumed.

Conclusion: The Centrality of Innovators and Early Adopters

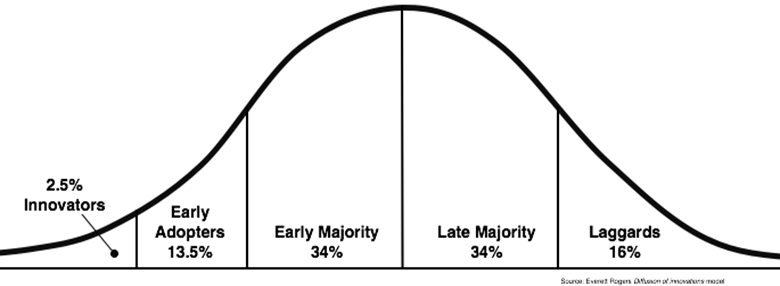

When we consider the revolutionary threshold framework for overthrowing oppressive regimes together with the five features of successful social movements, one thing stands out: the actions and characteristics of the first people and groups in a movement will determine its course. In his Diffusion of Innovation Theory, E.M. Rogers defines Innovators as those who are willing to be the first to try a new idea, product, or behavior; and he defines Early Adopters as those “who represent opinion leaders…enjoy leadership roles, and embrace change opportunities.”

Source: http://blog.leanmonitor.com/early-adopters-allies-launching-product/

We normally think of Innovators as people like Steve Jobs and Early Adopters as the first to buy a Tesla. But W.E.B. Dubois, Henry David Thoreau, Mahatma Gandhi, and James Farmer were also Innovators; and the early members of the NAACP, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the African National Congress were also Early Adopters.

So if the Innovators act in a way that lowers the revolutionary threshold, say by making the movement fun and giving Early Adopters a way to engage that is lower-risk, fun, and inclusive, it is more likely that the movement will spread to the general populace. We shouldn’t be surprised that places where social movements have succeeded have had charismatic, effective leadership and, often, have received specific training in nonviolent resistance. This is true in Ukraine, Serbia, South Africa, India, the Civil Rights Movements, and countless other examples.

While not everyone can be as dedicated as a Dr. King or a Gandhi, the good news is that not everyone needs to be. There are myriad ways to start or plug into movements and lower the threshold for the next person, who will in turn lower the threshold for the next person, and so on until victory. One can, for instance, close a bank account with Chase or Bank of America and open one with a bank that does not finance the climate crisis. Even better, if one turns this into a fun action in which others can participate–perhaps people can go en masse to a Chase bank branch and close their account while holding a fake oil barrel that says “I don’t want to pay for this anymore”–it becomes more likely that enough accounts will be closed as to force the bank to change their policies.

To answer our central question, we can say that movements fail when their leaders are unable to both lower the threshold to engagement and win a critical mass of people to the cause. Effective mass movements are triggered by individuals and small groups whose aims are taken up by more and more people, including, eventually, those with the power to achieve them.

As I’ve written before, nothing good ever happens by chance; it is not luck that drives the future, but concerted action by Innovators and Early Adopters. I find this immensely hopeful, for it means that anyone who so desires can play a pivotal role in building the world. The resources for achieving our ends are at hand–Gene Sharp, Erica Chenoweth, Beautiful Trouble, and others can give us the intellectual and practical framework for change. Then it’s up to us to put that framework into practice in the real world. What could be more exciting than that?

Leave A Reply